Introduction

Sometimes the financial markets seem to offer up a gift that seems “too good to be true”. The forces that tend to create these trading opportunities can take years (0r decades) to come together and they can last for years. These opportunities are almost always the result of investor greed and ignorance and unfortunately for you to win someone is losing big. More often than not they are not widely known about and are beyond the scope of most retail investors (or even retail brokers and advisers) because they require special knowledge or access to certain markets. Of all the financial markets, the bond market is unique in its ability to create opportunistic situations that are as close to “no lose” propositions as one will ever find in the financial markets – with a risk/return profiles almost impossible to find in any other financial asset. The reason lies in several features that are unique to the bond market such as poor pricing transparency and the extreme disappearance of liquidity during times of crisis. But the main reason bonds can provide opportunities that do not exist in any other asset class lies in the fact that as long as an issuer does not go bankrupt, an investor in bonds will receive the full face amount of the bond at maturity. This can create a “floor” or worst case return that no other financial asset can offer. For example, if Amazon stock plunged 70% it might seem like a bargain but there would be no guarantee that it could not go lower or even to zero. While the risk/return profile may seem fantastic, there would be no floor on how low my investment could go, no time frame for when it may pay off and no guarantee of a positive return. In my nearly 3 decade long career working in institutional bond sales and trading, I have seen the bond market offer up a few of these “too good to be true” setups and a quick review of these might offer some perspective on why I believe this current opportunity makes sense.

The 1994 “Bond Massacre” – In 1994, after years of consistently lowering interest rates, the Fed surprised the markets by beginning a rapid series of large rate increases sending bond prices plummeting. One specific structure type within the relatively new and still not fully understood collateralized mortgage obligation market was taking a real blood bath – the Inverse Floater. Inverse Floaters are floating rate bonds whose coupon has an inverse relationship to interest rates – as interest rates fall the coupon resets higher and vice-versa. It was a great play for years as rates fell and public funds rushed in to buy these bonds – many with coupons of well over 20%. Rising rates sent prices plummeting, dropping in some cases by over 50% in under 1 year. These bonds were backed by collateral that was guaranteed by agencies of the U.S. Government but headline risk and the massive, uniform exodus meant sellers couldn’t give them away. The coupons eventually went to zero – in a normal market these would have traded at a slight discount to zero coupon U.S. Treasuries but with heavily invested public funds going bankrupt and cutting services it was complete chaos. Sellers were forced to sell at the worst possible time and the bonds were trading at a fraction of their true value. Investors finally stepped in and began buying these bonds at significant discounts to their true value and were rewarded with years of double digit returns on agency guaranteed bonds.

The “Great Recession” or Credit Crisis of 2008 – Most people know that mortgages had something to do with the credit crisis and if you saw the movie “The Big Short” you probably have some understanding of the role securitization played in the crisis. CMO’s, CLO’s, and CDO’s – a veritable alphabet soup of securities backed by assets (mainly mortgages) containing shaky collateral that was often fraudulent began to go bad. As things began to unravel, firms like Bear Stearns were forced to shut their doors as investors rushed to dump their non-agency MBS/ABS. Normally the big brokerage firms would step up and bid the bonds but they were going bankrupt themselves leaving the market in complete disarray. Liquidity dried up and bond managers were told by their bosses to get rid of their mortgage and asset backed securities but there were almost no buyers. If you had to sell, your bond was worth whatever someone was willing to pay which had nothing to do with the true value of the underlying collateral. Investors with the proper valuation tools and knowledge were able to model the collateral, run various loss scenarios, and then bid bonds from desperate sellers at levels so far below their true value there was almost no way they could lose. Bonds traded at pennies on the dollar and it was as close to a license to steal as you will ever see in the financial markets – almost all the top performing hedge funds from 2009-2013 were heavily invested in these bonds.

curves going back 10 years (the bonds we will be discussing use the forward swap curve for their coupon calculations as opposed to the actual yield curve, we will be utilizing charts that show both and they tend to move together with a slight lag in the swaps curve). On the left you see the various swap curves (1-2, 2-3, 2-5, etc.) and the blue is their current spread (as of 5/17/2018). So you can see the 2’s to 10’s curve was 32.53 on that day. This is expressed in basis points which is 1/100th of 1%. Sounds complicated but all this means is that if you were to purchase a 10 year treasury you would receive .32% more than if you purchased a 2 year note. If you move to the right side of the table you will see that the 10 year historical high spread was 280 basis points or 2.8% (meaning you would get 2.8% more for buying a 10 year bond than a 2 year). The average has been 157 and the low was 17.49. Clearly we are currently near the lows. You can look at each curve for the historical information for that swap curve. If you look at the range column, the red mark represents average and blue is were we are now. You will note that nearly every curve is at historically low levels and several standard deviations away from the mean.

curves going back 10 years (the bonds we will be discussing use the forward swap curve for their coupon calculations as opposed to the actual yield curve, we will be utilizing charts that show both and they tend to move together with a slight lag in the swaps curve). On the left you see the various swap curves (1-2, 2-3, 2-5, etc.) and the blue is their current spread (as of 5/17/2018). So you can see the 2’s to 10’s curve was 32.53 on that day. This is expressed in basis points which is 1/100th of 1%. Sounds complicated but all this means is that if you were to purchase a 10 year treasury you would receive .32% more than if you purchased a 2 year note. If you move to the right side of the table you will see that the 10 year historical high spread was 280 basis points or 2.8% (meaning you would get 2.8% more for buying a 10 year bond than a 2 year). The average has been 157 and the low was 17.49. Clearly we are currently near the lows. You can look at each curve for the historical information for that swap curve. If you look at the range column, the red mark represents average and blue is were we are now. You will note that nearly every curve is at historically low levels and several standard deviations away from the mean. The current 2’s to 30’s yield curve (not swaps) is 57.60 basis points and you can see we have been in a straight line down since 2014 moving from over 300 basis points to 57. This means investors are currently receiving only .57% for locking in their money for an additional 28 years. Why would any sane person do that? The answer is speculation. If you are purchasing long bonds now you certainly aren’t doing it for the extra 57 basis points but because you believe rates will fall and the price of the long bond will increase. This generally happens when there is a crisis or a recession looming, so considering the trillions in long bonds that are outstanding a lot of people must have that view. Given the intervention of global central banks there are some other factors that have been driving spreads lower but the major reason is the belief that we will have low inflation and muted economic growth. If you take 30 seconds to study this graph, you will note the uncanny relationship between a flattening treasury curve and stock prices (represented by the yellow line). In every instance, you will note that as the curve has flattened stock prices have risen. It looks fairly muted in some periods due to the scale of the graph but lets look at a few data points for perspective. In the early 1990’s the curve was near 400 basis points and the Dow was around 2500. You can see as the yield curve fell from 400 basis points to its eventual low of -54 basis points (inverted), the Dow ran from 2500 to over 11,000. The yield curve made a low in March of 2000 and within months the Dow began a decline of about 30% to 7500. Notice how quickly the yield curve steepened, it went from -54 in march of 2000 to 270 in September of 2001. It took almost 10 years to fall and 1.5 years to move almost all the way back. In 2004 the curve peaked at 342 basis points and note that right as it began to fall the Dow made a major move up from 10,000 to almost 13,000 in 2 years from 2005-2007. Once again, within months of the curve bottoming, the stock market peaked and began a major decline during the credit crisis from 13,000 to around 7,000. Her again, notice how quickly the yield curve spiked up going from basically zero to over 250 in one year. Finally, notice where we sit today. The divergence between the yield curve and the stock market has never been higher and once again the curve appears to be forming a bottom. Certainly it could go lower and possibly invert over the short term, but if history is any guide we should be getting close to a bottom and once we hit bottom it won’t be long before we see a dramatic shift higher in the yield curve and a major move down in stocks. With this background, it is now FINALLY time to reveal the trade opportunity and analyze the actual bonds.

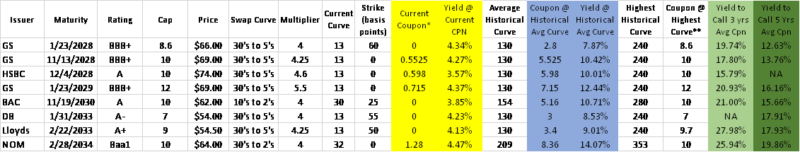

The current 2’s to 30’s yield curve (not swaps) is 57.60 basis points and you can see we have been in a straight line down since 2014 moving from over 300 basis points to 57. This means investors are currently receiving only .57% for locking in their money for an additional 28 years. Why would any sane person do that? The answer is speculation. If you are purchasing long bonds now you certainly aren’t doing it for the extra 57 basis points but because you believe rates will fall and the price of the long bond will increase. This generally happens when there is a crisis or a recession looming, so considering the trillions in long bonds that are outstanding a lot of people must have that view. Given the intervention of global central banks there are some other factors that have been driving spreads lower but the major reason is the belief that we will have low inflation and muted economic growth. If you take 30 seconds to study this graph, you will note the uncanny relationship between a flattening treasury curve and stock prices (represented by the yellow line). In every instance, you will note that as the curve has flattened stock prices have risen. It looks fairly muted in some periods due to the scale of the graph but lets look at a few data points for perspective. In the early 1990’s the curve was near 400 basis points and the Dow was around 2500. You can see as the yield curve fell from 400 basis points to its eventual low of -54 basis points (inverted), the Dow ran from 2500 to over 11,000. The yield curve made a low in March of 2000 and within months the Dow began a decline of about 30% to 7500. Notice how quickly the yield curve steepened, it went from -54 in march of 2000 to 270 in September of 2001. It took almost 10 years to fall and 1.5 years to move almost all the way back. In 2004 the curve peaked at 342 basis points and note that right as it began to fall the Dow made a major move up from 10,000 to almost 13,000 in 2 years from 2005-2007. Once again, within months of the curve bottoming, the stock market peaked and began a major decline during the credit crisis from 13,000 to around 7,000. Her again, notice how quickly the yield curve spiked up going from basically zero to over 250 in one year. Finally, notice where we sit today. The divergence between the yield curve and the stock market has never been higher and once again the curve appears to be forming a bottom. Certainly it could go lower and possibly invert over the short term, but if history is any guide we should be getting close to a bottom and once we hit bottom it won’t be long before we see a dramatic shift higher in the yield curve and a major move down in stocks. With this background, it is now FINALLY time to reveal the trade opportunity and analyze the actual bonds. Bond #1 is a Goldman Sachs with a maturity of 01/23/2028. The yellow shaded columns are the current coupon and the yield to maturity assuming the coupon never changes. This bond has a yield of 4.34% as a zero coupon for life. The 10 year treasury is currently 2.93% so the worst case yield on this bonds offers a spread of 1.41% over the treasury. The blue areas show the coupon and yield using the 10 year average swap rate (130bps), here the coupon would be 2.8% and the yield to maturity would be 7.87%. Using the historical widest curve in almost every case the coupon caps out. I did not run the yield to the maximum coupon because it is likely the issuer will call them at par ($100) as opposed to paying a 9+% coupon. This brings us to the green shaded areas. If we are nearing a bottom in the curve historically it doesn’t remain there long meaning we should be no more than a few years away from a dramatic steepening where these bonds hit their caps and likely get called generating 15%+ returns.

Bond #1 is a Goldman Sachs with a maturity of 01/23/2028. The yellow shaded columns are the current coupon and the yield to maturity assuming the coupon never changes. This bond has a yield of 4.34% as a zero coupon for life. The 10 year treasury is currently 2.93% so the worst case yield on this bonds offers a spread of 1.41% over the treasury. The blue areas show the coupon and yield using the 10 year average swap rate (130bps), here the coupon would be 2.8% and the yield to maturity would be 7.87%. Using the historical widest curve in almost every case the coupon caps out. I did not run the yield to the maximum coupon because it is likely the issuer will call them at par ($100) as opposed to paying a 9+% coupon. This brings us to the green shaded areas. If we are nearing a bottom in the curve historically it doesn’t remain there long meaning we should be no more than a few years away from a dramatic steepening where these bonds hit their caps and likely get called generating 15%+ returns.